.png)

January 12, 2026

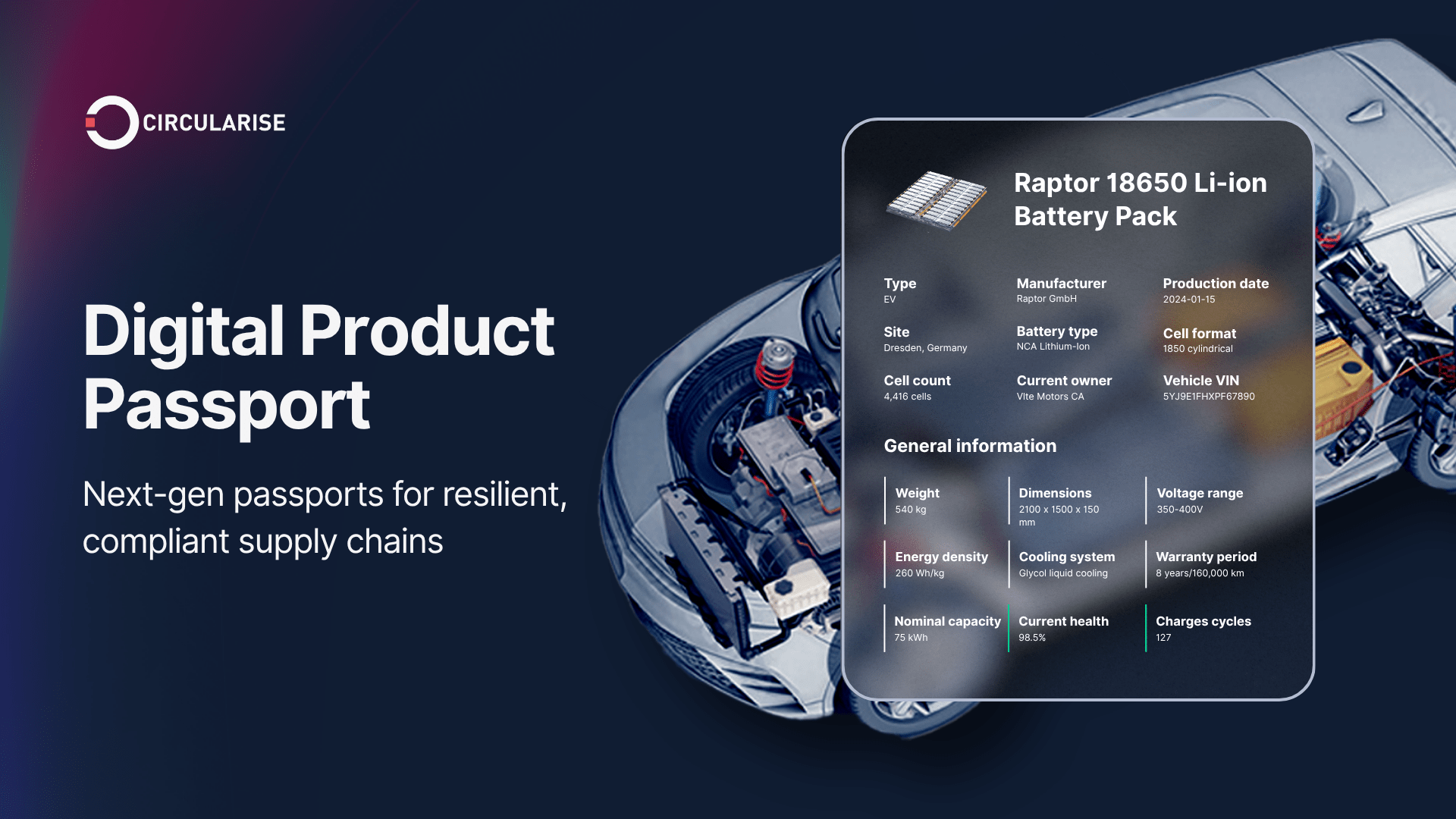

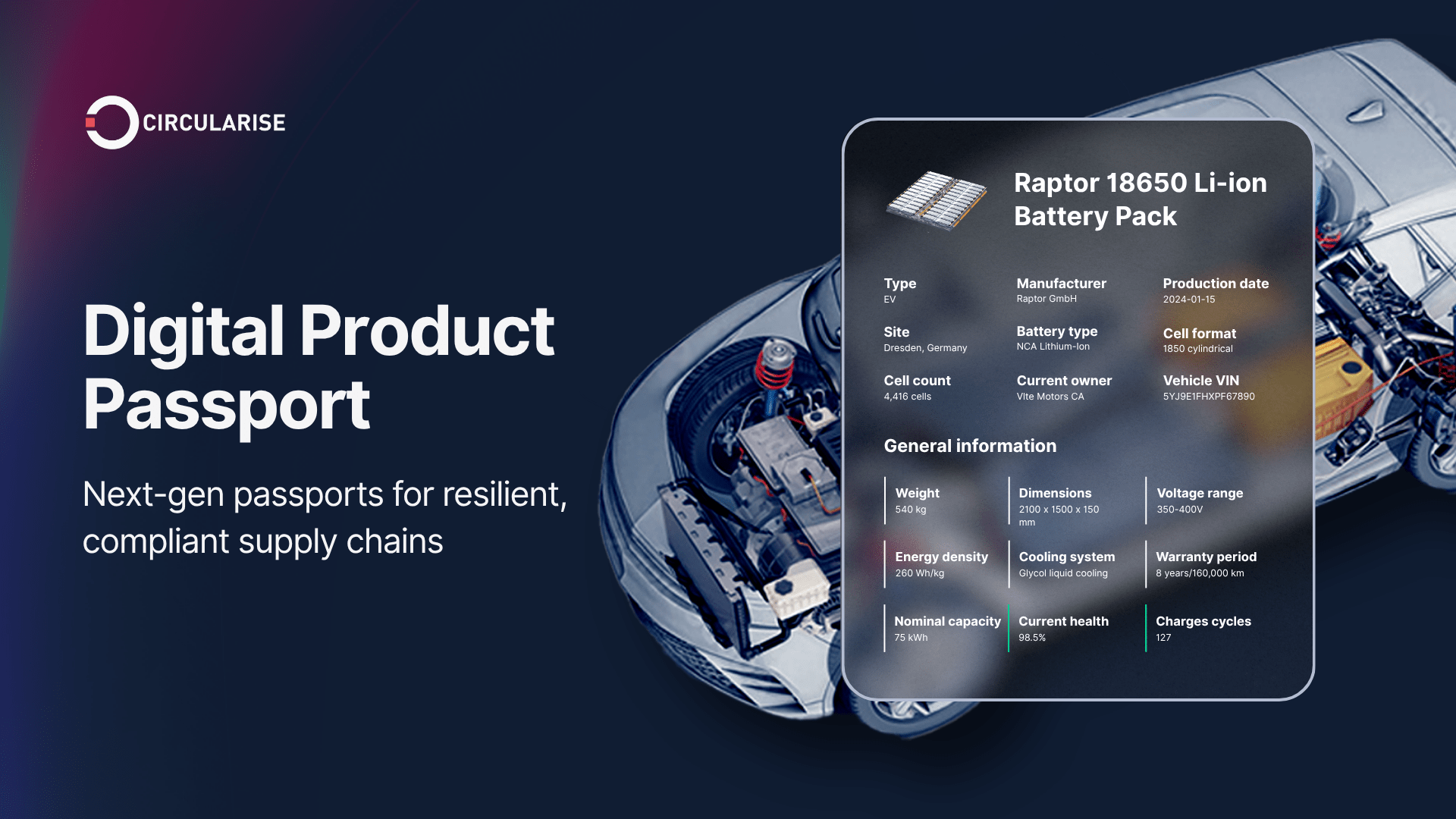

How to master tariffs with traceability: Unlock cost savings in your supply chain with Digital Product Passports (DPPs)

Ziva Buzeti

Policy Researcher

Digital product passports

December 18, 2025

Beyond compliance: How integrated traceability and LCA turn regulatory pressure into market advantage

Daniel Gregory

Project Manager

December 8, 2025

Tokyo Connect 2025: Circularise steps into a leading role in Japan’s sustainability transition

Trishna Menon

Senior Growth Marketer

October 9, 2025

Battery Regulation EU: Learn about battery passports

Chris Stretton

Growth Marketer @ Circularise

Digital product passports

October 9, 2025

EU battery passport regulation requirements

Chris Stretton

Product Marketer

Digital product passports

October 7, 2025

DPP upgrade: building a resilient and trade-ready supply chain

Igor Konstantinov

Head of Marketing

Digital product passports

September 18, 2025

Introducing Supplier Data Collection for direct supplier visibility

Igor Konstantinov

Head of Marketing

August 27, 2025

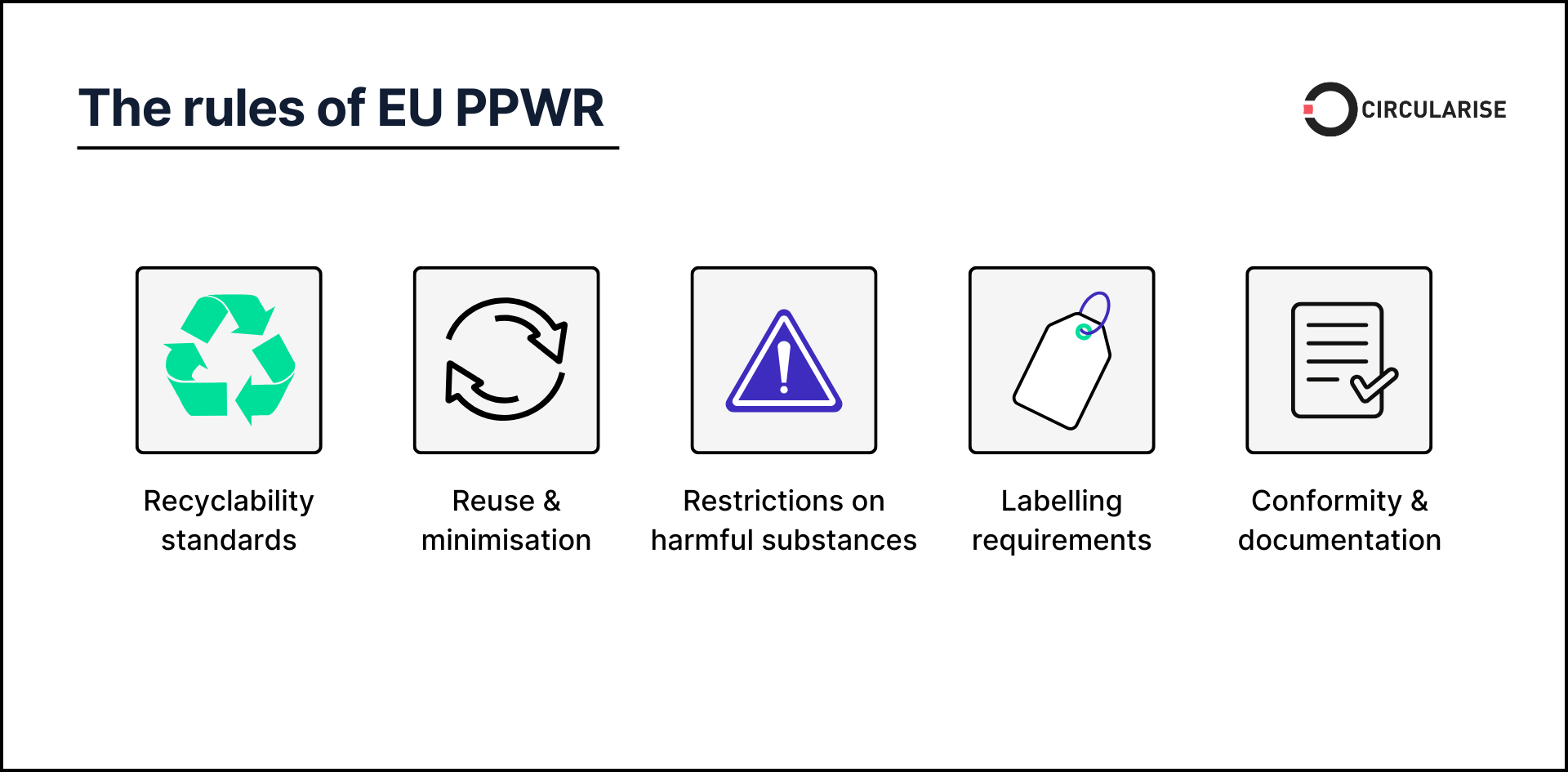

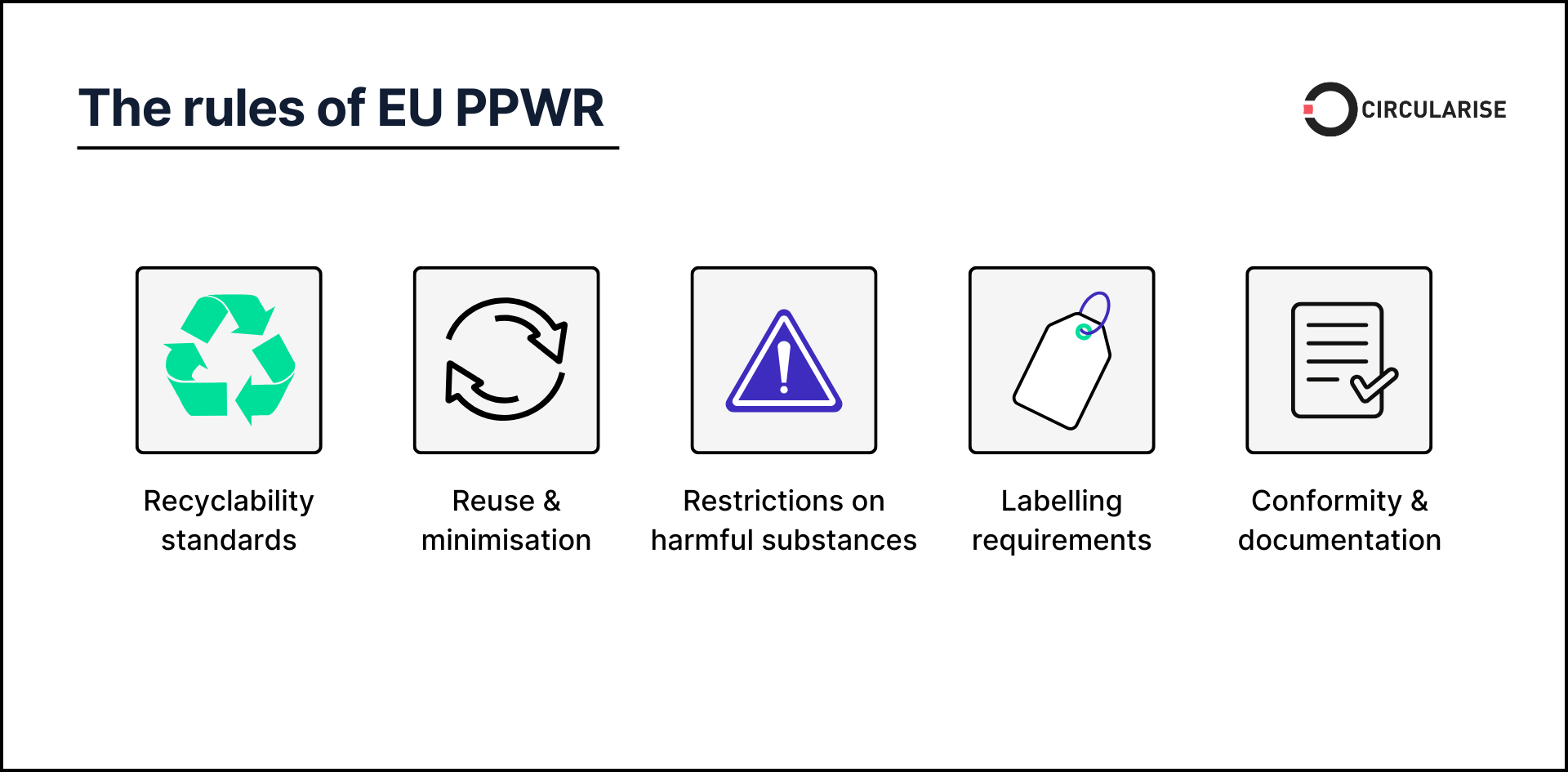

Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR): A guide to compliance, timelines, and mass balance solutions

Ziva Buzeti

Policy Researcher

August 19, 2025

Digital Product Passports (DPPs) required by EU legislation across sectors: ESPR, toys, detergents, batteries, and more

Ziva Buzeti

Policy Researcher

Digital product passports

August 4, 2025

Green incentives: Cash in on EU and UK low-carbon incentives (Part 2)

Tian Daphne

Senior Copywriter

.png)

.jpg)